Are You a Thermometer or Thermostat?

What would you think if I said that one of the project leader’s most important jobs is forecasting the future? I’m crazy? Out of touch? Yet it is absolutely true!

If a project schedule is not an accurate and reliable predictive tool, then what’s the point? If a detailed project schedule isn’t used to integrate, communicate and predictably ensure the on-time, sequenced contributions of project team members, then it’s nothing more than a simple calendar – sans the scenic photos.

At first pass this might sound a bit over the top, but consider this.

A project schedule is to a calendar, what a thermostat is to a thermometer. One simply reports the conditions while the other acts to actually control and predict conditions.

Only the thermostat has any meaningful value. Which do you want to be (alternatively, which are you?)

Your garden-variety project manager is charged with tracking the budget, updating the schedule, and hosting project status meetings. I would suggest that’s babysitting and not real project leadership.

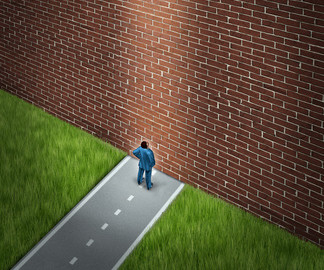

In the hands of a seasoned expert, the project schedule is a powerful predictive tool. It’s like a roadmap. Or a GPS navigational device. If it doesn’t help predict where you’re going, then exactly what’s the value? Much like a financial forecast, the value is not in telling you where you’ve been, but where you’re going to be. This is actionable information.

Knowing where you’ll be, when you’re going to be there, and what tasks are parts of the critical path is essential to confidently arriving at your target completion date. This knowledge will empower you to make critical business decisions and course corrections before it’s too late. It’s another key element of effective project preplanning.

A well honed project schedule also influences the project outcome.

You may recall from previous posts, that initial conditions are always the greatest indicator of final outcome. Thus an empirically derived schedule is a powerful tool. Consider this example situation.

A RECENT EXAMPLE

A client came to us at the end of last year. Their challenge – and our mission – was to get their new facilities designed, engineered, permitted and constructed – as well as their personnel relocated to the new facilities – before their lease expired. There was no way to know the magnitude of this undertaking without some analysis.

STEP ONE: OBSERVE

The first step towards influencing the project’s final outcome is to objectively observe and assess initial conditions. This is never more true that when it comes to the project schedule. The first thing to do is determine what the prospective schedule predicts. That is, when the fundamental tasks are linked in logical, predecessor-successor sequence, does that project schedule actually predict success? If you can’t make it work on paper, it’s not going to work in real-time.

STEP TWO: ASSESS

More importantly, the window of opportunity to make course-corrections or to take remedial steps is before the clock runs out, not after. Or to put it differently, “bad news doesn’t get better with age.” It’s better to find out now – while there is still some elbow to create new or revised schedule improvements.

STEP THREE: TAKE ACTION

In the case of this client, the data suggested that they would barely make the move-in date before their lease expired. However, instead of being viewed as bad news it was correctly interpreted as predicting success – but only if we started the project rolling ASAP.

MAKE THE CHANGE

One of the first steps with any project is not to just report out the “temperature”. It’s to predict the temperature and then set it at what you or your client wants it to be. YOU are the thermostat!

Taking this view of the project schedule will turbocharge your ability to stay on schedule and achieve all your project milestones.

Remember, it’s a project leader’s job to predict the future. Or as Yogi Berra said, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.”